Lopsided Success for Corporate Interests: The New Normal Under the Supreme Court’s Conservative Supermajority (2022-2023 Term)

Summary

Next week, the Supreme Court will hear its first arguments of the 2023–2024 term, a term that will present the Justices with a number of opportunities to make significant rulings benefitting corporate interests. This year’s docket already includes several potentially momentous cases that could hinder federal agencies’ ability to effectively implement the nation’s laws, along with efforts to constrict the taxation of the wealthy and make it harder to get into court over illegal discrimination.

In its most recent term, ending last June, the Court displayed its ongoing readiness to reshape the law in favor of big business, sometimes aggressively. Indeed, this appears to be the new normal under the helm of the Court’s conservative supermajority. We have long tracked the ascendance of corporate interests at the Supreme Court by examining how often the Court adopts the positions advocated by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s amicus briefs. Our report from last year summarized our most notable findings over the years. And the 2022–2023 term was fully in line with those trends.

In deciding which cases to hear last term, the Court overwhelmingly chose opportunities to help big business by reconsidering lower-court wins for individuals or the government. As usual, the Court rarely agreed to hear cases that would put corporate victories in jeopardy. And when resolving the cases it accepted for review, the Court ultimately ruled for corporate interests nearly three-fourths of the time, in some cases with dramatic results.

More specifically, with 13 wins and just 5 losses, the Chamber of Commerce prevailed in 72% percent of its cases.[1] This is above the 70% average that the Chamber has maintained under Chief Justice John Roberts.

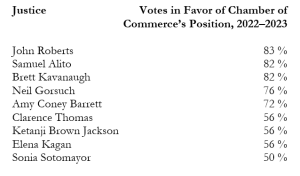

The Court’s ideological divide remained stark in business cases this term. Each of the more liberal Justices voted for the Chamber’s position roughly half of the time (as usual), while most of the conservative Justices did so much more frequently (as usual). Indeed, several conservative Justices sided with the Chamber more than 80% of the time:

Strikingly, for the second year in a row, Justice Clarence Thomas voted for the Chamber’s positions much less often than his conservative colleagues, this year aligning with the more liberal Justices. This is a departure from his long-term (pro-Chamber) record, and whether it represents an aberration or a shift remains to be seen. At the same time, however, Justice Thomas wrote and joined separate opinions suggesting a number of sweeping positions that would benefit corporate interests. Among them: striking down a federal fraud statute, prohibiting all agency adjudications that involve “private rights,” and—echoing a brief by the Chamber—ruling that the Constitution does not permit “qui tam” lawsuits, which date back to the Founding and help the government recover for fraud committed against it.

Notably, too, last term’s cases underscored that even when a conservative Justice breaks ranks and votes against the Chamber in a divided case, that alone does not suffice: with a 6-3 conservative supermajority, at least two conservative Justices must join any decision to get a majority ruling against corporate interests.

Just as important as the frequency of corporate victories in the 2022–2023 term was their scope, particularly in sharply divided cases. For instance, in Biden v. Nebraska, the conservative supermajority struck down the Biden administration’s student loan relief program while further entrenching the “major questions doctrine,” a judicial invention of recent decades that conservative and corporate advocates are trying to use to strike down a wide range of executive branch actions. In Sackett v. EPA, a 5-4 majority dramatically curtailed the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to protect wetlands, over Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s objection that the decision “departs from the statutory text, from 45 years of consistent agency practice, and from this Court’s precedents.” And in Coinbase, Inc. v. Bielski, a 5-4 majority gave a “windfall” (in the words of Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson) to defendants who seek to avoid accountability in court by enforcing arbitration agreements against consumers, employees, and others—allowing those defendants to automatically pause litigation in situations that were previously resolved case-by-case.

In decisions that were less divided or unanimous, corporate interests reaped additional gains. For instance, in Glacier Northwest, Inc. v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the Court made it easier for companies to sue labor unions over disputes arising from strikes, allowing those companies to short-circuit federal labor law procedures. In Twitter, Inc. v. Taamneh, the Court rebuffed efforts to hold tech companies accountable for allegedly harm-inducing material posted and promoted on their websites. In Axon Enterprise, Inc. v. FTC, the Court made it simpler to bring constitutional challenges to the actions of federal regulatory agencies, allowing such lawsuits to be initiated without waiting for completion of an agency’s administrative proceedings.

Meanwhile, in the few decisions that went against corporate interests last term, the Court often just maintained the status quo, declining to tilt the law even further in corporate America’s favor. To take one example, the Court gave a victory to employees in Helix Energy Solutions Group, Inc. v. Hewitt based on the unremarkable conclusion that a person who is paid by the day is not paid on “salary basis.”

The Court did, however, issue two notable rulings against corporate interests last term. Both were decided by an ideologically diverse five-Justice majority, were written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, and upheld state power against constitutional challenge. In National Pork Producers Council v. Ross, the Court rejected an industry effort to curtail state health and safety legislation under the “dormant Commerce Clause” doctrine. And in Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co., the Court permitted state courts to assert general jurisdiction over corporate defendants that have tacitly agreed to be sued in those states as a condition of doing business there.

While Ross and Mallory are important decisions, in each case the majority claimed it was merely following long-established precedent rather than making new law—in other words, preserving the status quo. To be sure, there is reason to question those claims: the Court arguably shrunk the dormant Commerce Clause doctrine in Ross, while Justice Amy Coney Barrett, writing in dissent, claimed that Mallory worked a “sea change.” But the scope of these decisions is debatable. And tellingly, even these anti-corporate rulings barely managed to squeak by, emerging from 5-4 decisions in which the Justices in the majority could not cohere around a single opinion, instead being forced to cobble together different pluralities of Justices. And as noted, both decisions involved challenges to state—not federal—power, a context in which conservative Justices have sometimes been more receptive to government interests.

With the federal government’s regulatory power squarely at issue in the cases to be argued this fall, corporate interests will have no shortage of opportunities for further success in advancing their agenda.

____________________________________________________________________________________

[1] The Chamber’s victories were Biden v. Nebraska; Bittner v. United States; Ciminelli v. United States; Coinbase, Inc. v. Bielski; Glacier Northwest, Inc. v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters Local Union No. 174; Jack Daniel’s Properties Inc. v. VIP Products LLC; Percoco v. United States; Sackett v. EPA; Slack Technologies, LLC v. Pirani; Twitter, Inc. v. Taamneh; Tyler v. Hennepin County; U.S. ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc.; and Axon Enterprise, Inc. v. FTC (which was decided alongside SEC v. Cochran). The Chamber’s losses were Helix Energy Solutions Group, Inc. v. Hewitt; Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co.; National Pork Producers Council v. Ross; Polselli v. IRS; and U.S. ex rel. Schutte v. Supervalu, Inc. One of the Chamber’s cases was dismissed without a decision (In Re Grand Jury) and two were decided in ways that did not resolve the issue addressed by the Chamber (Department of Education v. Brown and Gonzalez v. Google LLC). For purposes of our win-loss statistics, we chose to treat Axon Enterprise, Inc. v. FTC and SEC v. Cochran as a single case. Had we separated them, the Chamber’s win rate would be even higher: nearly 74%.