Drug Price Program Legal Fight Shifts Focus to Property Rights

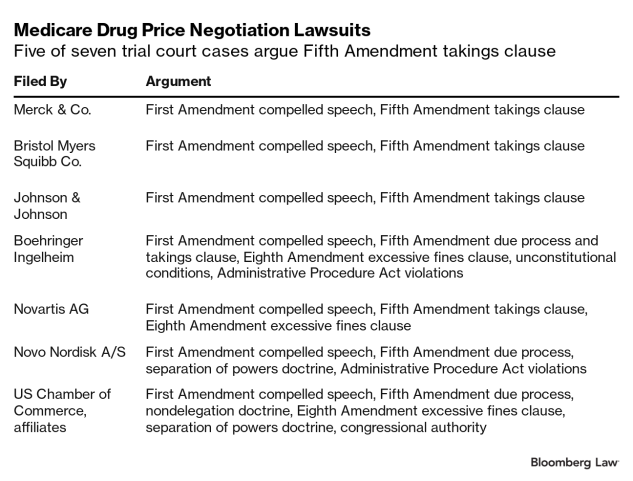

A recent US Supreme Court ruling on landowner property fees is getting drawn into the fight against a government drug price-setting program as drugmakers seek out additional defense against the negotiation scheme.

Merck & Co. and Bristol Myers Squibb Co. recently advised federal courts on the justices’ April 12 decision in Sheetz v. County of El Dorado in their respective legal battles against the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program.

Sheetz, as they wrote in supplemental authorities, supports their case because it “reiterates the basic proposition that ‘[w]hen the government wants to take private property,’ it ‘must compensate the owner at fair market value,’ and where the government ‘interfere[s] with the owner’s right to exclude others,’ that amounts to a ‘per se taking.’”

The pharmaceutical giants have long argued the price-setting scheme violates the takings clause enshrined in the Fifth Amendment because it seizes their property without paying just compensation. Their patented drugs are “protected from uncompensated takings,” they say.

As the takings clause has become the crux in lawsuits challenging the Biden administration’s top health initiative to reduce drug costs, manufacturers are finding ways to expand its scope. The industry has backed the argument with cases involving raisins, labor organizers, and now, landowner permit fees.

“When they read the Sheetz case, they see that yet another barrier has been removed to bringing a takings claim,” said professor Michael Allan Wolf of the University of Florida Levin College of Law, who specializes in property and takings law.

“The court has an organic view of the takings clause, and it keeps growing and growing and growing. I can’t blame an attorney for a pharmaceutical company for trying out the takings clause claim,” Wolf said.

Takings Arguments

The Supreme Court in Sheetz addressed the question on if the Nollan/Dolan test—a framework on whether permit conditions have a “nexus” and “rough proportionality” to the government’s land-use interest—recognizes a distinction between legislative and administrative conditions on land-use permits. The Nollan/Dolan test comes from Nollan v. California Coastal Commission (1987), and Dolan v. City of Tigard (1994), two earlier Supreme Court cases that limited the government’s ability to impair property interests with land use regulations.

The court on April 12 held that it doesn’t recognize a distinction, but the justices are sending the case back to the California Court of Appeals to answer if the traffic impact fee at issue is a taking.

Manufacturers say Sheetz explains that Nollan/Dolan is “modeled on” and “rooted” in the “unconstitutional conditions doctrine.” That doctrine applies to their argument because if the program’s “‘access’ mandate ‘would be a compensable taking if imposed’ directly, then imposing it as a condition on Medicare coverage requires ‘application of Nollan/Dolan scrutiny,’” the drugmakers wrote.

While this isn’t the first time manufacturers have brought up Nollan/Dolan scrutiny, their recent filings are a “very strained application to go from land-use to a government contract negotiation,” said Shelley Ross Saxer, a professor at Pepperdine University Caruso School of Law.

Saxer, who specializes in property and land-use law, said pharmaceutical companies can argue the program is a taking, but the Nollan/Dolan framework isn’t the right test to determine that.

“I understand the government is saying we’re going to pay you so much less than your business model, but if you want to challenge that legislation as going too far—restricting too much—Penn Central is your test,” she said.

The test, born out of Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City (1978), requires courts to balance three factors to determine if a regulatory taking occurred: economic impact of the regulation on the claimant; the extent to which the regulation interferes with distinct investment-backed expectations; and the character of the government action.

“The difference is what test you apply to the taking,” Saxer said. “Every property owner wants to allege a per se taking—such as under Nollan/Dolan scrutiny—but I don’t believe it is the appropriate test in this situation.

However, manufacturers defended the framework in drug-pricing showdown oral argument before the US District Court for the District of New Jersey in March.

If the court disagrees with manufacturers on the nexus proportionality and remove the Nollan/Dolan test, “it’s still clear that the baseline unconstitutional conditions test would apply,” Kevin King, partner at Covington & Burling LLP, said at the argument on behalf of Johnson & Johnson.

“In other words, you take the thing that’s a condition, you make it mandatory, and you decide whether it’s constitutional,” King said.

The Department of Justice, representing the Department of Health and Human Services, reiterated in its responses to Merck and Bristol Myers that the “Supreme Court had made clear” that the Nollan/Dolan test is reserved for the special application of land-use permits, and “nothing in Sheetz suggests that the high court was overruling that precedent.”

Raisins, Union Organizers, and Drugs

Sheetz adds to Merck and Bristol Myers’s list of Supreme Court decisions used to defend that the program results in a per se taking, which is backed by a tax penalty if manufacturers refuse to comply with the program.

They frequently cite Horne v. Dep’t of Agric. (2015) in their briefings, a case where the high court determined a taking occurred when a statute directed farmers to turn over a percentage of their raisin crop without charge. They also cite Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid (2021), which held that a California law requiring labor organizers’ access to agricultural employers’ property was a per se physical taking.

But “it’s not surprising that Big Pharma would connect their arguments to Sheetz,” said Nina Henry, counsel at the Constitutional Accountability Center, who filed an amicus brief in Sheetz and some of the drug pricing cases.

“All of these cases are examples of how the conservative legal movement is trying to stretch the boundaries of the takings clause far beyond what its text and history support,” Henry said.

Merck and Bristol Myers are also still “grasping at straws here,” because “negotiating drug prices is different from zoning or land use laws,” said Andrew Twinamatsiko, director of the Health Policy and the Law Initiative at Georgetown University’s O’Neill Institute.

“All the other courts that have addressed this specific issue in the drug negotiation context—and Medicare writ large—have been clear that drug companies do not have a property interest in Medicare because participation in Medicare is voluntary,” Twinamatsiko said.

Nonetheless, manufacturers have signaled on taking their challenges to the Supreme Court as the program forces them to agree with a “government-dictated” price and threatens innovation to bring life-saving treatments to the market.

“Attorneys representing business interests are always looking for that hook in the Constitution that they can grab to get the court’s attention—increasingly that is the takings clause,” Wolf said.