The Arc of Constitutional Progress

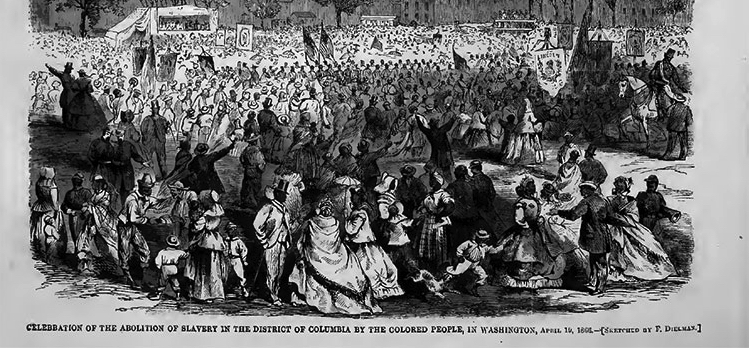

America’s Constitution is, in its most vital respects, a progressive document, written by revolutionaries and amended by We the People who prevailed in the most tumultuous social upheavals of our Nation’s history. The Reconstruction Republicans after the Civil War (our nation’s Second Founding), the Progressives and the suffragists in the early 20th century, and the civil rights and student movements in the 1950s and 1960s all successfully amended our Constitution to extend its rights and protections to more Americans. This timeline explores the people, places, and events that have shaped the arc of progress of our nation’s founding document.

The Founding Era: Articles of Confederation Give Way to the Original Constitution, Bill of Rights

Articles of Confederation adopted by Continental Congress

Articles of Confederation ratified by all thirteen states

Our nation’s first form of government, which established a “firm league of friendship” between thirteen independent states, proved flawed. Congress had some powers, but no means to carry them out and no power to tax individuals or legislate upon them. This created such an ineffectual system of government that it nearly cost Americans victory in the Revolutionary War. George Washington lamented that “unless Congress speaks with a more decisive tone; unless they are vested with power by the several States competent to the great purposes of War . . . our Cause is lost.” The dysfunctional government of the Articles of Confederation lead the Founders of our Constitution to press for a new national charter, which granted Congress broad powers to solve national problems.

Constitutional Convention convenes in Philadelphia, PA

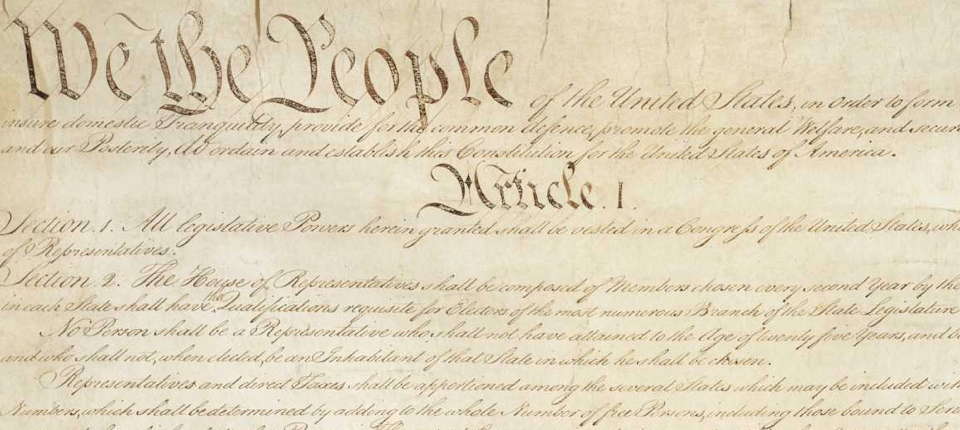

Constitution signed by convention delegates

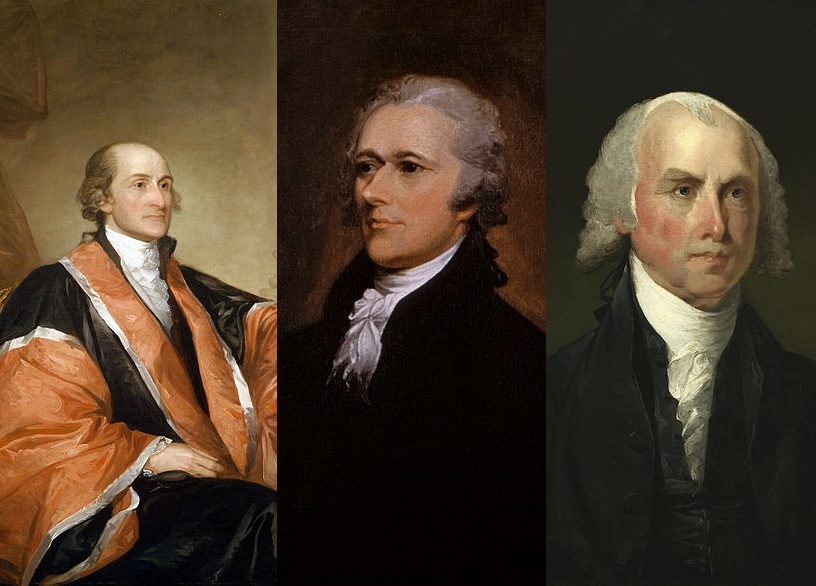

Federalist Papers

John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison write a series of 85 essays—known as the Federalist Papers—urging the American people to ratify the Constitution.

Constitution ratified

The Constitution was approved by “We the People” following votes in specially-elected ratifying conventions held in the thirteen states. As Professor Akhil Amar has explained, “[i]n the late 1780s, this was the most democratic deed the world had ever seen.”

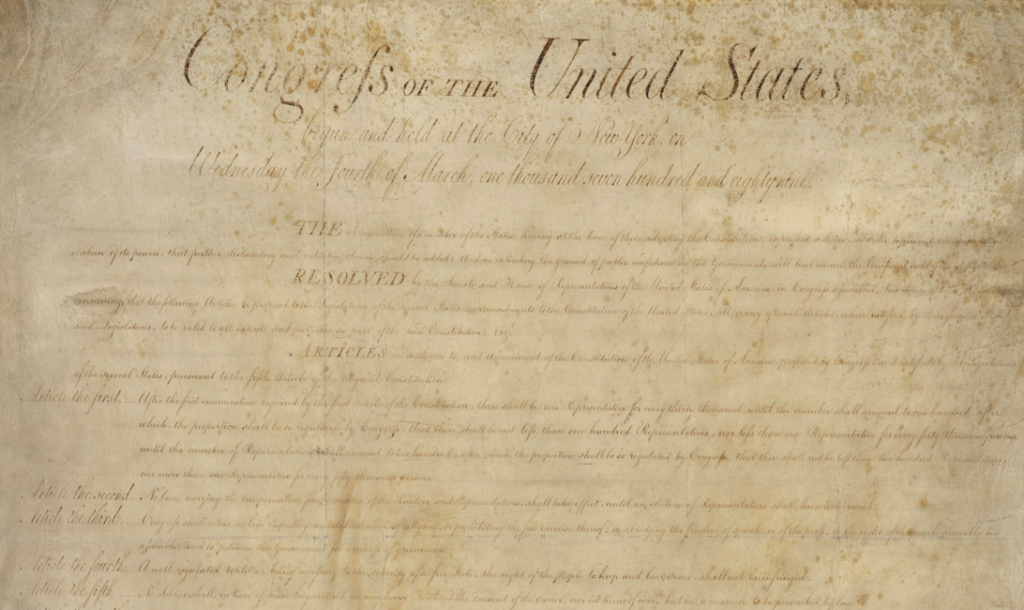

Bill of Rights passed by Congress

Bill of Rights ratified

Many had opposed the original Constitution because it lacked a Bill of Rights protecting the fundamental rights of all Americans. The first Amendments added to the Constitution corrected this defect. As James Madison explained, these Amendments “expressly declare the great rights of mankind secured under this constitution,” establishing a heritage of liberty that all Americans treasure.

America's Second Founding: Civil War and Reconstruction

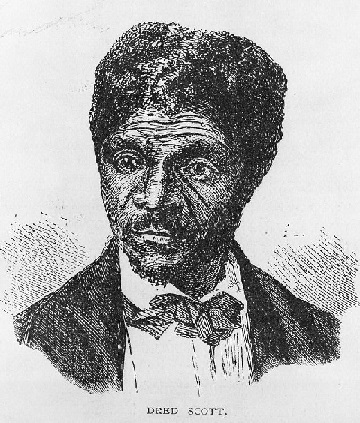

Dred Scott v. Sanford decided

Dred Scott, perhaps the worst decision in the Supreme Court’s history, held that African Americans, whether slave or free, were not citizens under the Constitution. Although this holding disposed of Dred Scott’s plea for freedom, the Court went on to find a fundamental constitutional right to hold slaves, which guaranteed to slave owners the right to take slaves into any new territories in the country. These holdings were two sides of the same coin – both were driven by the Court’s belief that African Americans had “no rights which the white man is bound to respect.” Dred Scott led to the Civil War and monumental changes to the Constitution.

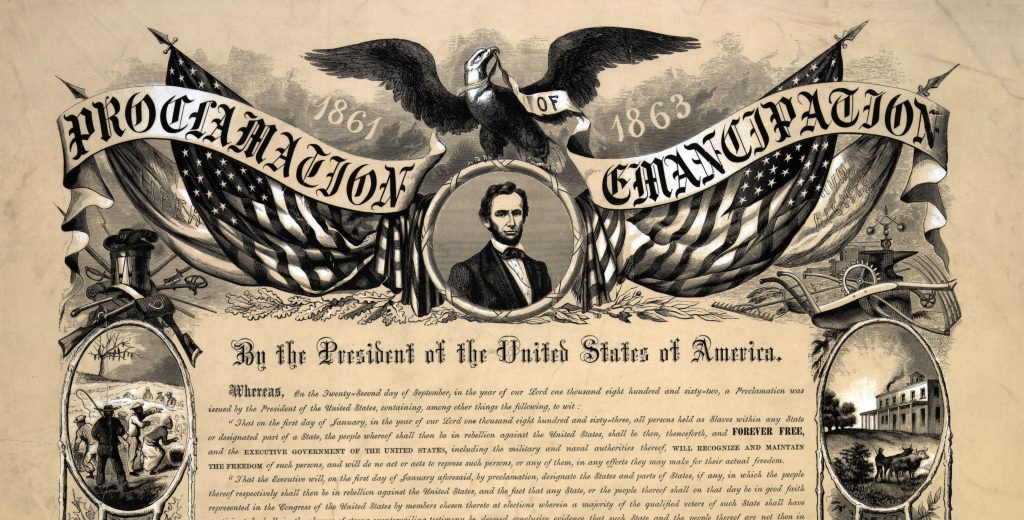

Lincoln issues Emancipation Proclamation

“On this day, Lincoln finalized the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all slaves in rebel lands–some three million souls–to be ‘forever free.’ With the stroke of the executive pen, Lincoln changed the meaning of the war and the course of American history. No longer was the struggle merely one to restore the Union as it was. Henceforth, it would be a war for Freedom alongside Union.” — Professor Akhil Amar

Bill to abolish slavery by constitutional amendment introduced in House

Bill introduced by Ohio U.S. Representative James Mitchell Ashley.

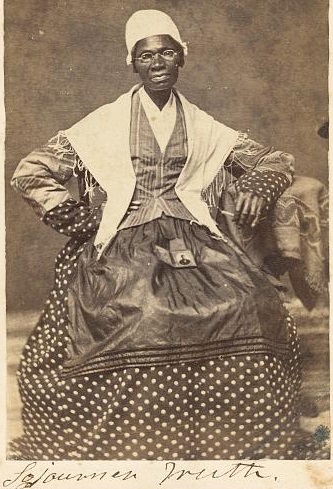

In 1863, a writer from Iowa wrote a letter to the Editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard, relaying their observation of Sojourner Truth’s comments on the Constitution:

I was once present in a religious meeting where some speaker had alluded to the government of the United States, and had uttered sentiments in favor of its Constitution. Sojourner stood, erect and tall, with her white turban on her head, and in a low and subdued tone of voice began saying, “Children, I talks to God and God talks to me. I goes out and talks to God in de fields and de woods. [The weevil had destroyed thousands of acres of wheat in the West that year.] Dis morning I was walking out, and I got over de fence. I saw de wheat a holding up its head, looking very big. I goes up and takes holt ob it. You b’lieve it, dere was no wheat dare? I says, God, [speaking the name in a voice of reverence peculiar to herself]; what is de matter wid dis wheat? and he says to me, “Sojourner, dere is a little weasel in it.” Now I hears talkin’ about de Constitution and de rights of man. I comes up and I takes hold of dis Constitution. It looks mighty big, and I feels for my rights, but der aint any dare. Den I says, God, what ails dis constitution? He says to me, “Sojourner, dere is a little weasel in it.” The effect upon the multitude was irresistible.

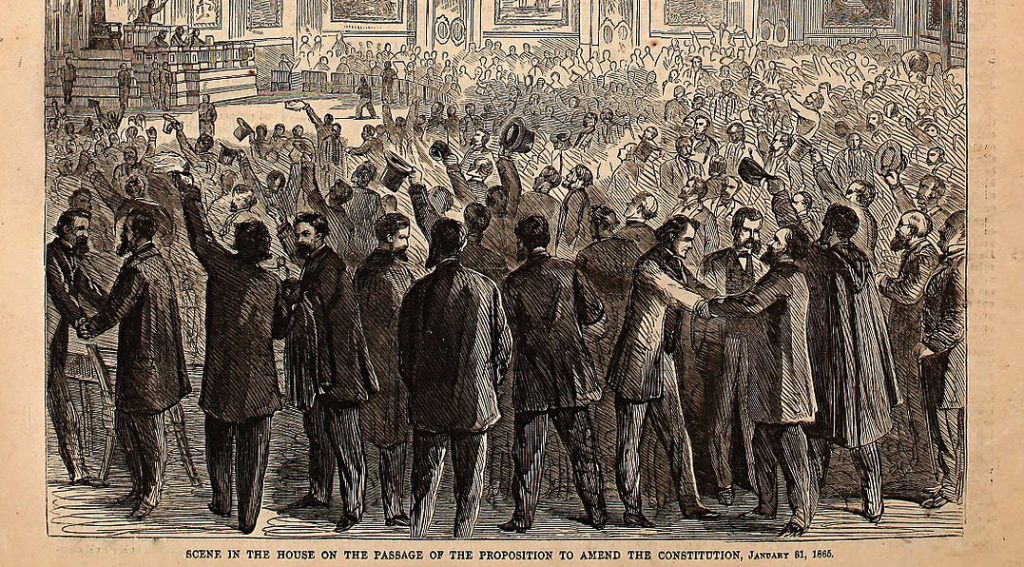

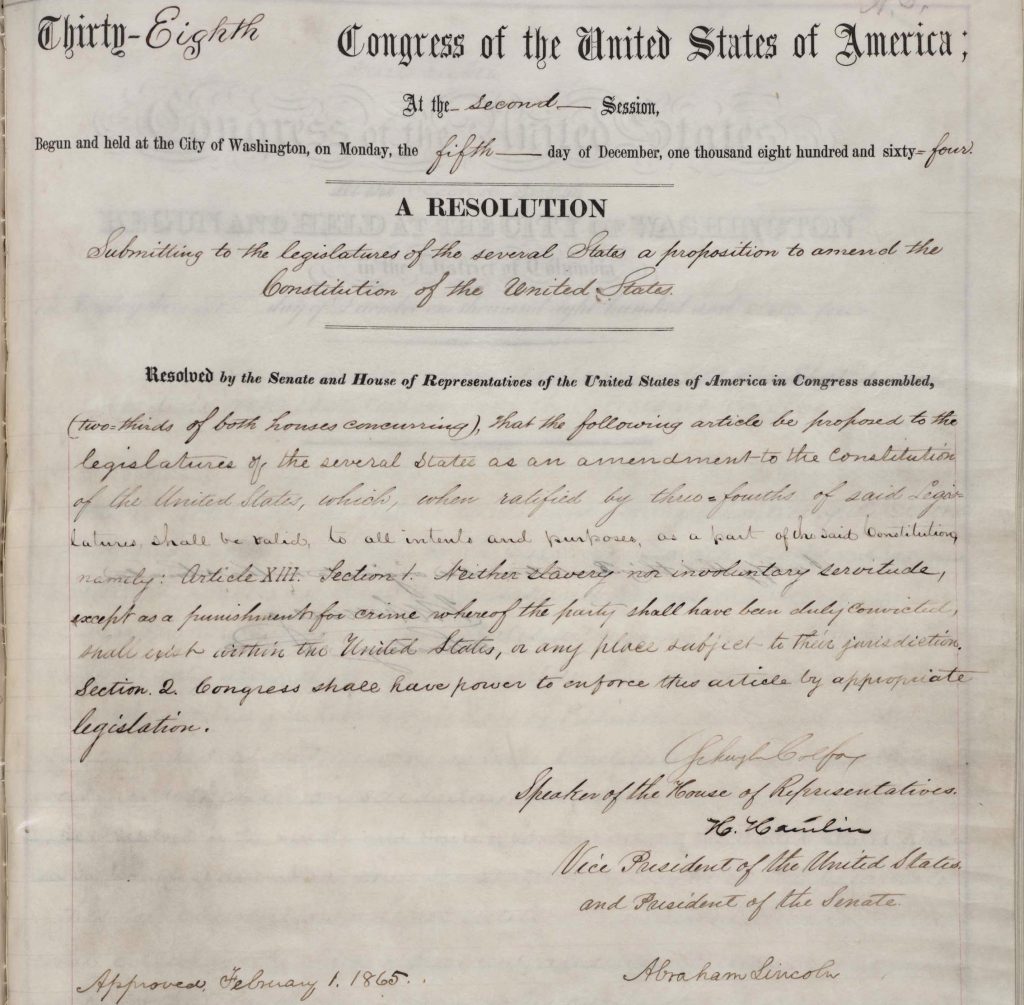

Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing chattel slavery, approved by Congress

President Lincoln signs the Thirteenth Amendment

For Lincoln, the Thirteenth Amendment was critical to settling “the fate” of slavery “for all coming time—not only for the millions now in bondage, but for unborn millions to come.” “Abolishing slavery by constitutional Amendment” would resolve all constitutional difficulties by eliminating slavery outright and provide Congress with authority to enforce this new constitutional command. Following the Amendment’s approval by Congress, Lincoln took the unusual step of signing the Amendment before sending it along to the states for ratification, calling it a “King’s cure” for the evil of slavery.

The Thirteenth Amendment, however, created an exception to the prohibition against slavery, allowing it “as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” That, in turn, paved the way for the practices of convict leasing and debt peonage, and unpaid and underpaid involuntary prison labor to this day. CAC supports efforts to #EndTheException by ratification of the Abolition Amendment.

Thirteenth Amendment ratified

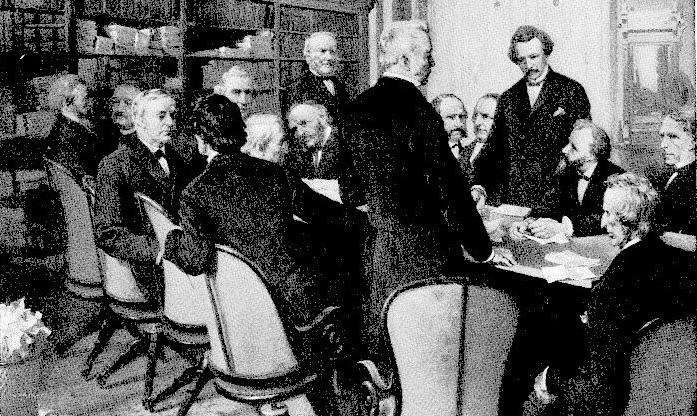

Joint Committee on Reconstruction formed

The Joint Committee on Reconstruction was formed to investigate conditions in the Southern states. Based on these investigations, the Joint Committee would draft the Fourteenth Amendment.

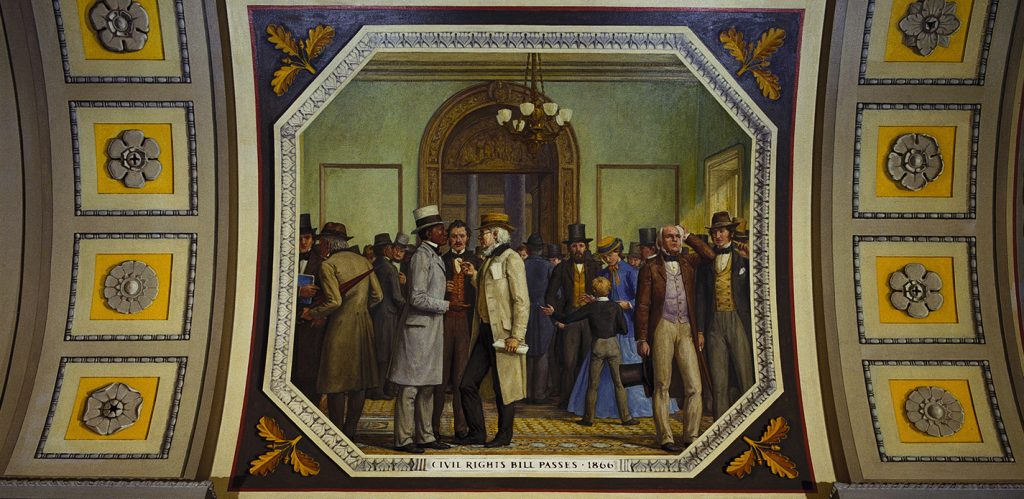

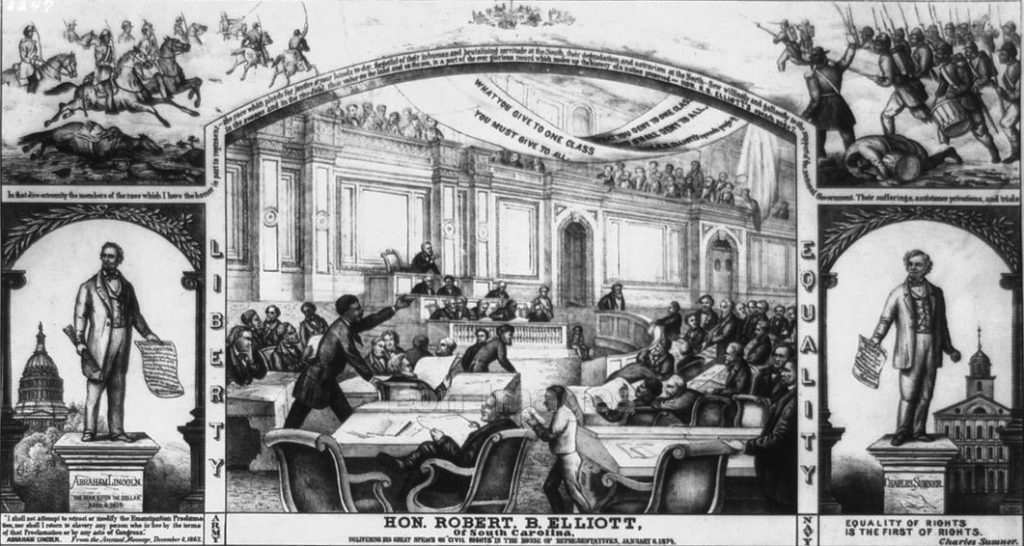

Civil Rights Act of 1866, the nation’s first federal civil rights law, passed

Fourteenth Amendment approved by Congress

As described by Eric Foner, the nation’s leading historian on Reconstruction, the Fourteenth Amendment’s “language . . .transcended race and region,” “challenged legal discrimination throughout the nation and changed and broadened the meaning of freedom for all Americans.”

Joint Committee on Reconstruction issues report urging ratification of Fourteenth Amendment

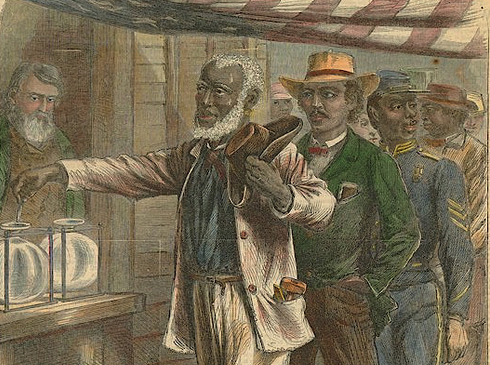

Reconstruction Act of 1867, which granted the right to vote to African American men in former states of the Confederacy, becomes law

Fourteenth Amendment ratified

Fifteenth Amendment, prohibiting racial discrimination in voting, approved by Congress

“Slavery is not abolished,” argued Frederick Douglass, “until the black man has the ballot.”

Fifteenth Amendment ratified

Together, the three Reconstruction Amendments—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth—fundamentally altered our Constitution, abolishing slavery, requiring states to respect substantive fundamental rights and equality, and guaranteeing the right to vote free from racial discrimination. These Amendments represent a Second Founding of the Constitution, erasing the stain of slavery from our charter.

Congress passed Civil Rights Act of 1875

The Progressive Era

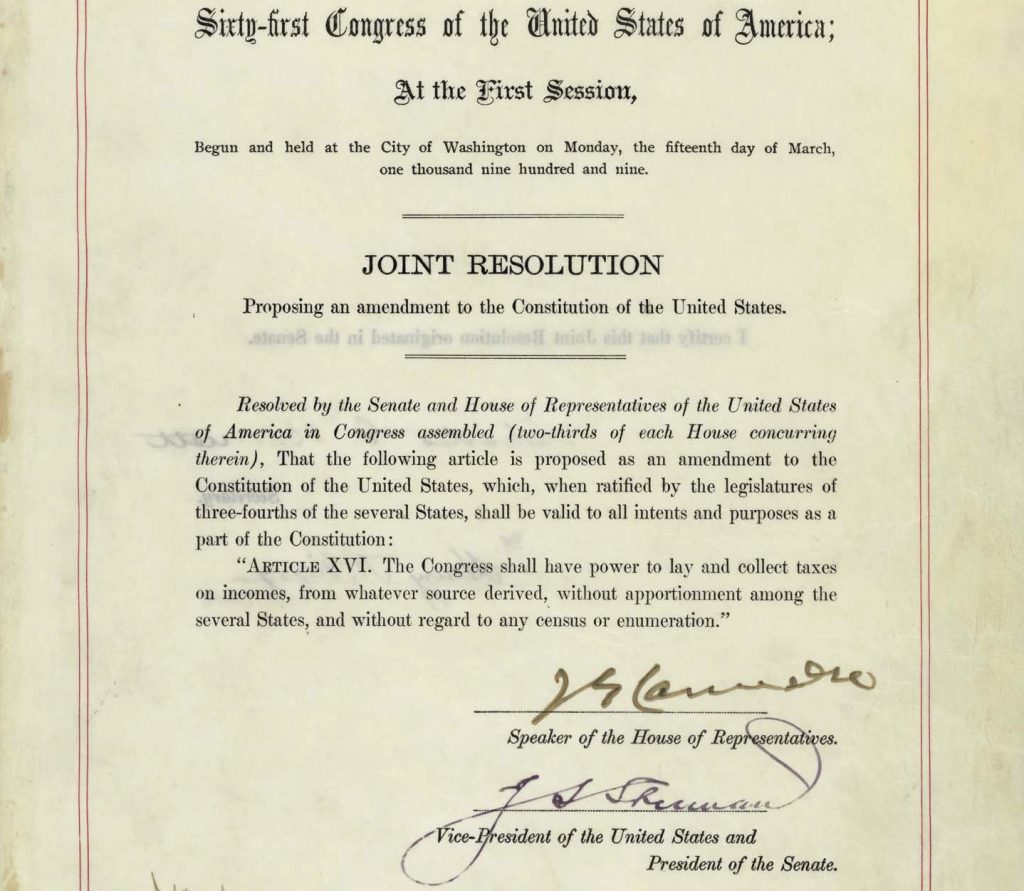

Sixteenth Amendment, giving Congress the power to collect an income tax, approved by Congress

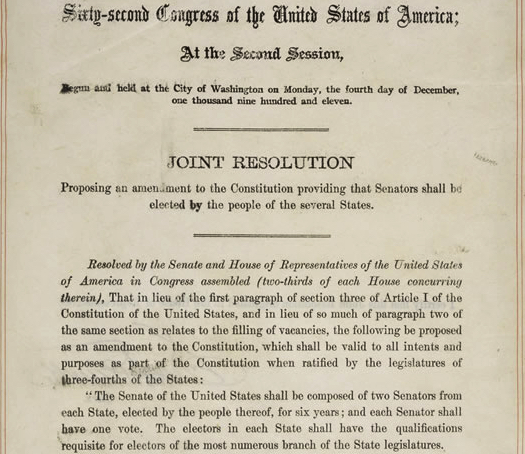

Seventeenth Amendment, guaranteeing the right to vote for U.S. Senators, approved by Congress

The effort to give the people the right to choose U.S. Senators was the product of a long struggle. Between 1874 and 1912, Congress received 175 petitions from state legislatures around the country calling for direct election of Senators. Despite this, the Senate repeatedly refused to approve the Amendment. By 1910, 27 states petitioned Congress for a constitutional convention, and only the threat of an actual convention finally spurred the Senate to approve the Amendment.

Sixteenth Amendment ratified

Seventeenth Amendment ratified

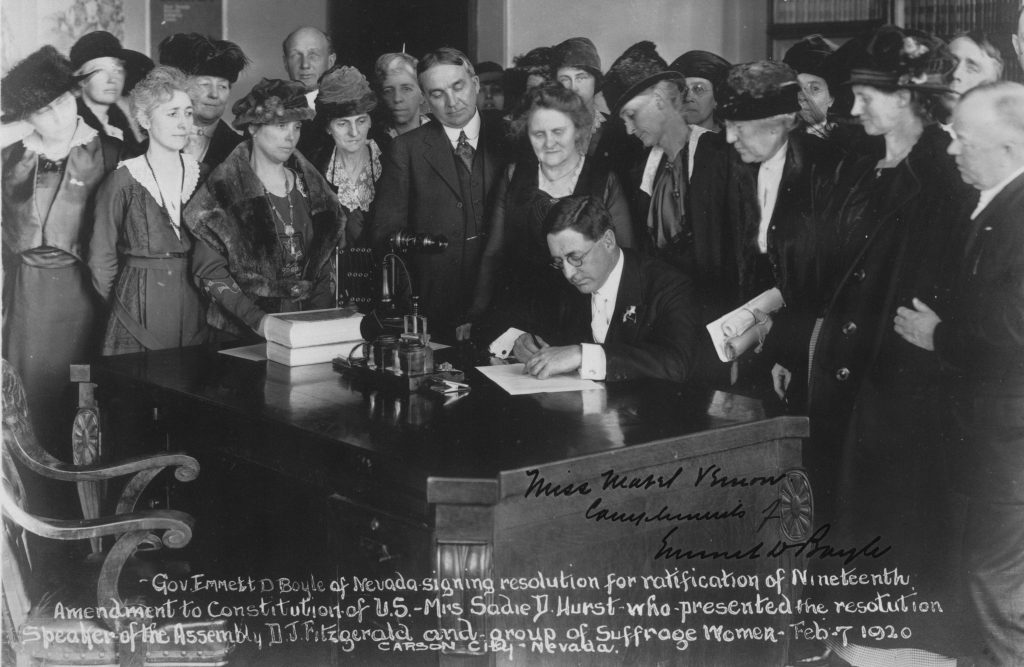

Nineteenth Amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote, approved by Congress

Nineteenth Amendment ratified

With the ratification of the Sixteenth, Seventeenth, and Nineteenth Amendments, Professor Akhil Amar has written, “early-twentieth-century Americans reaffirmed two of the main themes of the Reconstruction Amendments—nationalism and equality—and extended them to new contexts.” The Sixteenth Amendment explicitly gave Congress the power to collect an income tax, rejecting conservative attacks on the income tax as an illegitimate form of wealth redistribution. The Seventeenth Amendment gave citizens the right to vote for U.S. Senators, while the Nineteenth Amendment granted women the right to vote. As Amar describes, “some ten million women who had never been allowed to vote in a general election became the full political equals of men,” making the addition of the Nineteenth Amendment “the single biggest democratizing event in American history.”

This seismic change did not come easily. As Carrie Chapman Catt observed, “[t]o get the word ‘male’ out of the Constitution cost the women of the country fifty-two years of pauseless campaign…. [T]hey were forced to conduct fifty-six campaigns of referenda to male voters; 480 campaigns to urge suffrage amendments to voters; 47 campaigns to induce State constitutional conventions to write woman suffrage into State constitutions; 277 campaigns to persuade State party conventions to include women’s suffrage planks; 30 campaigns to urge presidential party conventions to adopt woman suffrage planks in party platforms; and 19 campaigns with 19 successive Congresses.”

The Struggle for Civil Rights and Voting Rights

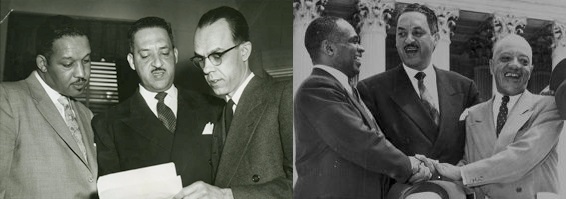

Brown v. Board of Education decided

Brown, the culmination of a brilliant legal strategy engineered by Thurgood Marshall, helped breathe new life into the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection and end Jim Crow’s system of racial oppression. It overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, which had approved Jim Crow segregation and disregarded the Fourteenth Amendment’s meaning.

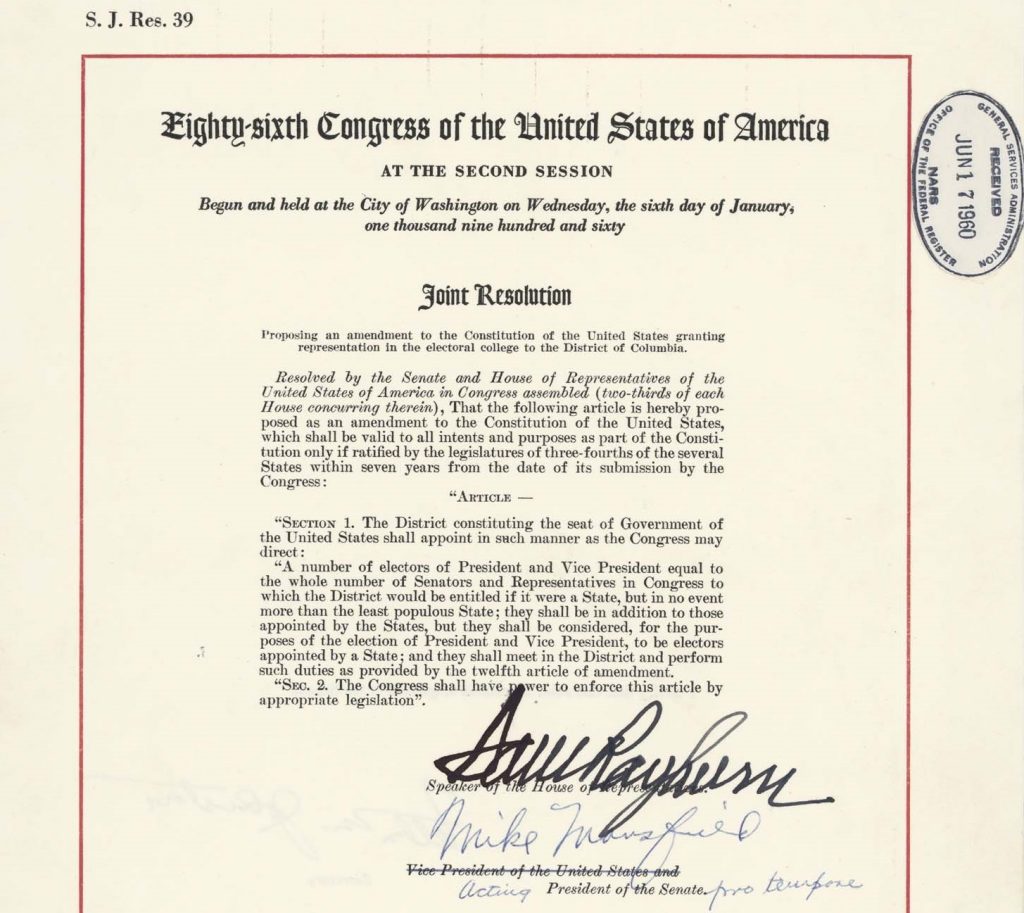

Twenty-Third Amendment, granting right to vote for presidential electors to citizens residing in the District of Columbia, passed by Congress

Twenty-Third Amendment ratified

Twenty-Fourth Amendment, eliminating poll taxes in federal elections, passed by Congress

Iconic civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer described for the magazine The Nation how the poll tax was part of the systematic state obstruction that prevented her and other African Americans from voting in Mississippi, via reporter Jerry DeMuth:

According to Mississippi law the names of all persons who take the registration test [on their knowledge of the state constitution, as a precondition to being registered] must be in the local paper for two weeks. This subjects Negroes, especially Delta Negroes, to all sorts of retaliatory actions. “Most Negroes in the Delta are sharecroppers. It’s not like in the hills where Negroes own land. But everything happened before my name had been in the paper,” Mrs. Hamer adds.

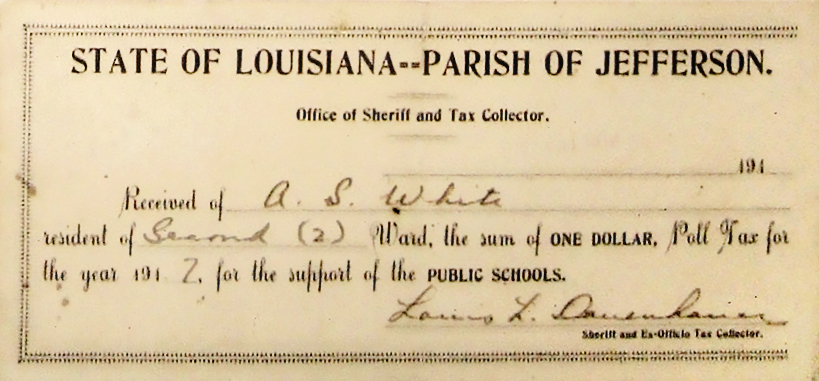

She didn’t pass the test the first time, so she returned on December 4, and took it again. “You’ll see me every 30 days till I pass,” she told the registrar. On January 10, she returned and found out that she had passed. “But I still wasn’t allowed to vote last fall because I didn’t have two poll-tax receipts. We still have to pay polltax for state elections. I have two receipts now.”

After being forced to leave the plantation, Mrs. Hamer stayed with various friends and relatives. On September 10, night riders fired sixteen times into the home of one of these persons, Mrs. Turner. Mrs. Hamer was away at the time….

Twenty-Fourth Amendment ratified

A few years before the above poll tax receipt was issued in Louisiana, one observer remarked that the poll tax system in another Deep South state, Georgia, was “the most effective bar to Negro suffrage ever devised” (later quoted by Justice Ginsburg in her dissent in Miller v. Johnson). Such receipts became obsolete after the Twenty-Fourth Amendment was ratified, making unconstitutional such obstruction of the ballot box according to one’s ability to pay a tax. Another example, from Arkansas in 1957, is available here.

Civil Rights Act of 1964 signed into law

Helping to realize the Fourteenth Amendment’s command of equality, “the Civil Rights Act of 1964 barred racial discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and virtually all federally funded activities, including education, and also prohibited discriminatory activities based on other characteristics such as gender, religion, and national origin. Women’s equality was introduced by fiat. The Act’s ban on ‘sex’ discrimination in employment was actually added by a Southern Democrat in the House in an attempt to derail the bill. … [S]ince its initial passage, the Act has been amended periodically in ways that strengthen its reach and enforcement mechanisms, rendering it our Nation’s most comprehensive civil rights legislation.” — Professor Sheryll Cashin

Voting Rights Act of 1965 signed into law

“In 1965, only a year after the Anti-Poll Tax Amendment became part of the Constitution, Congress enacted a landmark Voting Rights Act targeting a host of electoral tests and devices designed to disenfranchise blacks. Though this act was hardly limited to poll-tax suffrage laws, it surely encompassed them… Explicitly invoking its own authority to enforce the Reconstruction Amendments, Congress directed the attorney general to seek judicial invalidation of such laws.” — Professor Akhil Amar

Twenty-Sixth Amendment, granting the right to vote to young adults, passed by Congress

Twenty-Sixth Amendment ratified

As reflected in the Twenty-Third, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Sixth Amendments, modern reformers have continued the push to make our democracy more inclusive. As Professor Akhil Amar describes, “[y]oung adults and poor people won additional rights of democratic participation, as did residents of the nation’s capital city.” As a result of the hard work of Americans during Reconstruction, the Progressive era, and the late 20th century, the right to vote is protected by more provisions of the Constitution than any other right.