The Art of Suffrage: Cartoons Reflect America’s Struggle for Equal Voting Rights

Content Warning to Readers: Some quotations of image captions in this post contain offensive and derogatory terms used at the times these images were produced, and underscore the obstacles of racism and sexism with which those fighting for the right to vote were confronted.

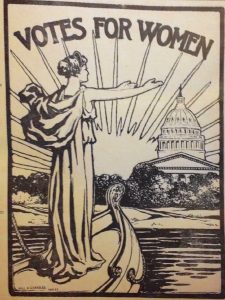

Photo Credit: William Henry Chandler, “Votes for Women,” The Suffragist, November 22, 1913, 1.

Photo Credit: William Henry Chandler, “Votes for Women,” The Suffragist, November 22, 1913, 1.

The battle for women’s suffrage in the United States has a long, complex, and fascinating history, bound up in civil rights struggles that stretched across race and class. Over the last two centuries, women fought to amend a Constitution whose Framers didn’t include their wives and daughters – let alone the enslaved people whose involuntary labor they depended upon[1] – in their vision of citizenship.[2] Clearly, ensuring that the protections promised in our Constitution extend to everyone is still an ongoing struggle. Despite this year’s historic election, the second in four years to have a woman campaigning for President or Vice President, millions of women in America still face countless barriers to exercising their right to vote.[3]

The complexity of the fight for women’s suffrage is vividly depicted in art, from elegant, idealized engravings of women as national saviors to crudely misogynist cartoons that ridiculed the cause.[4] The improved printing technology[5] and faster mail of the 19th and early 20th centuries also enabled these images to spread widely.[6] Thus, arguments over suffrage – both serious and satirical – often took place in the political cartoons of the day, and these images influenced public opinion as women fought to participate in politics.[7]

Race and the Ballot

As in most mainstream print culture near the turn of the century, racist caricatures abounded as the nation debated immigration policies and citizenship for different groups, especially Native Americans,[8] Chinese Americans,[9] and Black Americans.[10]

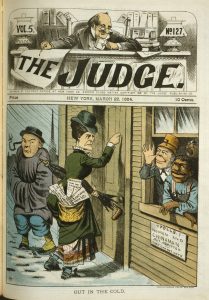

“Out in the cold,” a cartoon splashed across the cover of an 1884 issue of The Judge, portrayed these prejudices and social divisions.

Photo credit: Grant E. Hamilton, Out in the cold, March 22, 1884, The Library of Congress.

Photo credit: Grant E. Hamilton, Out in the cold, March 22, 1884, The Library of Congress.

In this image, an Irish man thumbs his nose at the white woman and Chinese man excluded from the polls, and a Black man looks on with a contented expression, portrayed by the artist as apparently satisfied with his easy access to voting — which fails to reflect the reality of the violence and repression that Black voters faced from the white power structure in the decades following the Civil War.[11] The sign below the two men in the window makes the point clear, reading “POLLS: Women and Chinaman [sic] Not Admitted. They cannot vote.”

Many similar images, like some white suffragists themselves, focused on the supposed injustice of white women being denied the ballot while Black men and European immigrant men were not[12] – but this artist did note that Chinese men were also excluded from the political process.[13] The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed in 1882, was the first legislation to specifically target one ethnic group, severely restrict their entry into the United States, and prohibit them from obtaining citizenship once they were in the country.[14]

As immigration historian Robert Barde points out, the Act “was intended to end the arrival of Chinese laborers into the United States and to bar Chinese from naturalization,” and “[o]nly certain classes of Chinese were even allowed to enter the United States.”[15] Despite such discriminatory policies, Chinese American women like Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee took a prominent place in the fight for suffrage[16] – even though she, like most Chinese Americans, would remain barred from voting until the Act was repealed in 1943.[17]

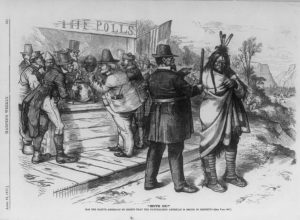

The plight of Native American men was also visually dramatized, as in this 1871 Thomas Nast drawing that shows a Native man denied entry to the polls and told to “MOVE ON!” The caption asks, “Has the Native American no rights that the naturalized American is bound to respect?”[18] Nast’s language here appears to pointedly echo the Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857, where Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote that Black people “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”[19]

The National Museum of American History’s Behring Center states that throughout “the 19th and early 20th centuries, most Native Americans were classified as members of sovereign nations or dependents under guardianship of the U.S. government. Neither were citizens and neither could vote. Even those who were U.S. citizens could not vote in all states.” According to the Behring Center, this particular image shows the “hypocrisy of enfranchising naturalized immigrants and not the country’s original inhabitants.”[20] The contrast depicted in this cartoon between the experiences of European immigrants — so recently arrived, yet able to participate in democracy as citizens — and the oppression faced by the original inhabitants of North America, is stark.

Photo credit: Thomas Nast, “Move on!” Has the Native American no rights that the naturalized American is bound to respect?, 1871, The Library of Congress.

Photo credit: Thomas Nast, “Move on!” Has the Native American no rights that the naturalized American is bound to respect?, 1871, The Library of Congress.

As in much of the era’s imagery, women of color are literally left out of the picture – even though Black American, Chinese American, and Native American women all advocated for voting rights and full citizenship in battles that extended decades after the Nineteenth Amendment’s ratification.[21]

As historian of women’s suffrage imagery Allison K. Lange points out, art depicting women of color exercising their right to vote is rare, reflecting their lack of resources compared to the white women who were more easily able to shape the public image of the women’s movement.[22] But one stunning cartoon in a 1916 issue of The Crisis,[23] a magazine published by the NAACP, dramatizes Black women’s role at the forefront of the struggle for civil rights and full citizenship.[24]

Titled “Woman to the Rescue!”, it depicts a Black woman wielding a club representing the “Federal Constitution” and protecting her little children clinging to her skirts from the vultures of “Jim Crow Law” and “Segregation.” The “Grand-father Clause” lies defeated at her feet, a reference to the 1915 Guinn v. United States decision[25] that struck down laws, common in the post-Reconstruction South, exempting whites from the literacy tests that frequently disenfranchised Black Americans.[26] Historian of Black women’s suffrage Martha S. Jones argues that, for Black women, “ratification of the 19th Amendment was not a guarantee of the vote, but it was a clarifying moment . . . Black women were the new keepers of voting rights in the United States.”[27]

The third vulture menacing her from a distance is labeled “Seduction,” a clear reference to the sexual predation and violence that Black women often faced – without the protection of assumed purity that was usually accorded to white women.[28]

Image Credit: John Henry Adams, “Woman to the Rescue,” The Crisis 12, no. 1 (May 1916): 43.

Image Credit: John Henry Adams, “Woman to the Rescue,” The Crisis 12, no. 1 (May 1916): 43.

The figure of the Black man running from the confrontation appears to satirize the Black Americans who prioritized economic stability over civil rights. His speech reads, “I don’t believe in agitating and fighting. My policy is to pursue the line of least resistance. Tsh – with Citizenship Rights I want money I think the white folk will let me stay on my land as long as I stay in my place — (shades of WILMINGTON, N.C.). The good whites aint responsible for bad administration of the law and lynching and peonage, — let me think awhile: er –”

This character’s contradictory thinking reflects, in a caricatured fashion, some of the disagreements among Black activists at the time about the best methods to attain equality. This divide was exemplified in the decades of debate between two of the most prominent Black leaders of the period, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois. Founder of the Tuskegee Institute and advisor to multiple presidents, Washington focused on the need for Black Americans to attain economic security and thus prove their worthiness as citizens.[29] Dubois, on the other hand, founded the NAACP partly due to his disagreements with this approach. In “The Souls of Black Folk,” his groundbreaking civil rights text, he criticized Washington for asking Black people to “give up, at least for the present” both “political power” and “insistence on civil rights.”[30]

Activists and artists like those who contributed to The Crisis were working to organize Black Americans in an atmosphere of brutal repression, which ranged from limited political and economic opportunities in a time of increased segregation[31] to the horrific violence of the Wilmington Massacre. That 1898 insurrection ended with a newspaper office burned to the ground, the local government overthrown and taken over by white supremacists, and at least sixty Black people murdered.[32] The reference to Wilmington in “Woman to the Rescue!”, then, appears to be a pointed reminder to any Black men who assumed that the “good whites” would leave them alone if they kept to the path of “least resistance” and avoided civil rights activism.

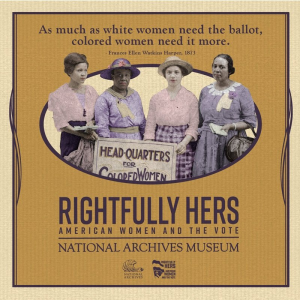

Throughout the nineteenth century, prominent Black women speakers and activists like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper[33] and Sojourner Truth[34] had long refused to bow their heads to such rhetoric. Decades before this cartoon was published, Watkins Harper directly challenged the white women who narrowly focused on their own fight for suffrage.[35] She was the only Black woman to speak on the platform alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony at the 1866 National Women’s Rights Convention, where she pointed out that “justice is not fulfilled so long as woman is unequal before the law.”[36]

In the late 1860s, conflict over the Fifteenth Amendment, and what it meant for newly freed Black men to vote when white women could not, exposed the racist fault lines among white suffragists who preferred to put themselves first.[37] But even before the Civil War, Sojourner Truth’s 1851 speech, “Ain’t I a woman?”, pushed back against the popular image of white women as delicate and angelic creatures and centered the long-ignored humanity of Black women.[38] Watkins Harper’s critique of the rosy utopia often predicted by white suffrage advocates[39] was clear-eyed and even humorous in tone: “I do not believe that white women are dew-drops just exhaled from the skies. I think that like men they may be divided into three classes, the good, the bad, and the indifferent.”[40]

Watkins Harper was a political visionary who pushed for an America that still has not yet come to pass, proclaiming that “we are all bound up in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse of its own soul.” She demanded the inclusion of Black women as part of “one great privileged nation.”[41] 21st-century archivists and activists have worked to better represent the reality of Black women’s presence in the fight for suffrage, as in this poster by the National Archives.

Photo credit: Robyn Muncy & Marjorie Spruill, Wilson Center Alumni Lead Women’s Suffrage Exhibit at the National Archives, Wilson Center, June 27, 2019. Courtesy of the National Archives Museum.

Photo credit: Robyn Muncy & Marjorie Spruill, Wilson Center Alumni Lead Women’s Suffrage Exhibit at the National Archives, Wilson Center, June 27, 2019. Courtesy of the National Archives Museum.

Idealizing Womanhood

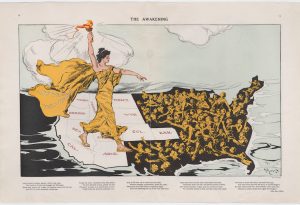

The idea of respectable womanhood played a major part in visual depictions of suffragists, and in making the cause of suffrage more palatable to a nation politically controlled by white men.[42] Images showing glorious strength and moral righteousness, like the allegorical figures of Liberty and Justice that often appeared in pro-suffrage art, used neo-classicism to show white women as avatars of the nation’s highest ideals.[43] One iconic 1915 map showed “Votes For Women” as a Lady Liberty-like figure, bringing the light of change east from the Western states that had already enacted suffrage.

Photo credit: Henry Mayer, “The Awakening,” Puck Magazine, February 20, 1915, 14-15.

Photo credit: Henry Mayer, “The Awakening,” Puck Magazine, February 20, 1915, 14-15.

In this gloriously colorful print from the UK-based Women Writers’ Suffrage League, a woman appeals to a winged and haloed Justice, sword and scales at the ready, for protection from “Prejudice,” depicted as a man attempting to haul her back by her sash.

Photo credit: W. H. Margetson, “London Women Writers’ Suffrage League Postcard,” Women Writers’ Suffrage League, 1909 (detail). Courtesy of the Krystyna Campbell-Pretty and Family Suffrage Research Collection.

Photo credit: W. H. Margetson, “London Women Writers’ Suffrage League Postcard,” Women Writers’ Suffrage League, 1909 (detail). Courtesy of the Krystyna Campbell-Pretty and Family Suffrage Research Collection.

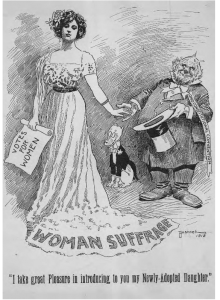

Imagery in support of suffrage also invoked white women’s traditional place as mothers, wives, and daughters. When suffragists in Ohio began to campaign for a women’s suffrage amendment to the state constitution in 1912,[44] one cartoon showed “Woman Suffrage” as a beautiful “Newly-Adopted Daughter” and the Convention as a doting father, beaming with pride.

Photo credit: Elmer Bushnell, Women’s suffrage political cartoon, 1912. Courtesy of Ohio History Connection.

Photo credit: Elmer Bushnell, Women’s suffrage political cartoon, 1912. Courtesy of Ohio History Connection.

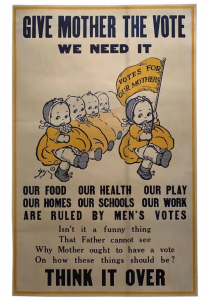

Motherhood was also central to these appeals, with the cute little babies of Rose O’Neill, creator of the famous Kewpie dolls, clamoring to “Give Mother The Vote!”[45]

Photo credit: Rose O’Neill, “Give Mother the Vote: We Need It,” 1915. Courtesty of The New-York Historical Society and the Rose O’Neill Foundation.

Photo credit: Rose O’Neill, “Give Mother the Vote: We Need It,” 1915. Courtesty of The New-York Historical Society and the Rose O’Neill Foundation.

Pushing for Reform in a Society Divided by Class

Throughout the Progressive Era, many women worked to change society by reforming areas that were traditionally coded as feminine, like education and caring for the poor.[46] Rose O’Neill’s poster points out the need for women’s oversight of “food, health, schools, and homes,” especially where children were concerned.

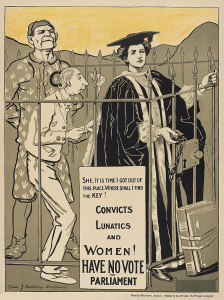

As the nineteenth century progressed, women – mostly privileged and white, but not exclusively[47] – also pushed to access higher education in greater numbers.[48] Across the Atlantic, British artists like Emily Harding contrasted women who had recently begun to rise through academia with disenfranchised “lunatics and convicts,” portraying many suffragists’ frustration with their second-class status – although at the expense of other marginalized groups.[49]

Photo credit: Emily J. Harding Andrews, “Convicts lunatics and women! Have no vote for parliament She: Is it time I got out of this place – Where shall I find the KEY?,” Artists’ Suffrage League, 1890, Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo credit: Emily J. Harding Andrews, “Convicts lunatics and women! Have no vote for parliament She: Is it time I got out of this place – Where shall I find the KEY?,” Artists’ Suffrage League, 1890, Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Today, this 1890 image of an educated woman wearing a cap and gown imprisoned with a “convict” and “lunatic” shows the social stratification and eugenics policies that were endemic on both sides of the Atlantic[50] — and serves as a reminder that millions of people with felony convictions are still barred from voting in America.[51]

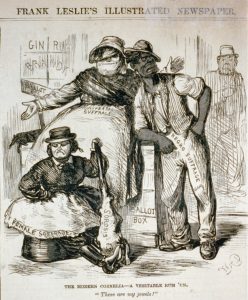

Class anxieties, as well as the endemic racism discussed above, were central to the national battle over suffrage. One 1869 cartoon referenced “Cornelia’s Jewels”, a folktale about a Roman matron whose true treasures were her sons,[52] to satirize the principle of universal suffrage.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, “The modern Cornelia, a veritable rum ‘un”, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1869. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, “The modern Cornelia, a veritable rum ‘un”, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1869. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“Universal Suffrage” is depicted as “The Modern Cornelia,” a hard-drinking, lower-class woman who proudly shows off “Negro Suffrage” and “Female Suffrage” as her children. “Female Suffrage” is a squat woman in a shortened skirt and riding boots, whose mean countenance and knobby club labeled “Sorosis” (sisterhood), seem to threaten violence while mocking the very idea of women’s political power.

Cartoons like these negatively linked suffrage for Black Americans with women’s suffrage, and used the supposed absurdity of Black people and women voting to make jokes or prophesy the certain downfall of the nation if such people were allowed to participate in politics. Journalist Elaine Weiss points out that “the rage and backlash unleashed by the [Nineteenth] amendment’s expansion of voting rights and promise of a more inclusive democracy should not be ignored.”[53]

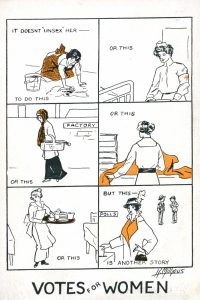

The labor movement was also integral to the fight for suffrage. Pro-suffrage artists like Katherine Milhous, as in this 1915 postcard, contrasted the reality of women’s work with society’s fear of upper-class white women becoming tainted by political participation.[54] If women weren’t “unsexed” by hard work, whether as cleaners, nurses, waitresses, or factory workers, then why should voting invalidate womanhood?

Photo credit: Katherine Milhous, “Votes for Women,” 1915. Courtesy of Rod Library at the University of Northern Iowa.

Photo credit: Katherine Milhous, “Votes for Women,” 1915. Courtesy of Rod Library at the University of Northern Iowa.

Misogyny and Ridicule

White men frequently satirized the concept of women’s suffrage.[55] Many men also simply believed that women were simply unfit to participate in democracy. Nearly fifty-five years before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, a New York Times editorial utterly dismissed the idea of women’s suffrage by asking if women were not “really better governed by the average prudence and business sense of men,” and deriding women’s “lack of judgment and of decision.”[56]

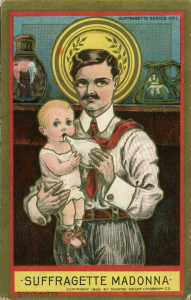

As seen in the images below, anti-suffragists appeared convinced that a country where women participated in politics was a nation where women wore pants, men were forced into the home, and chaos reigned.[57]

Photo credit: Artist unknown, Suffragette Madonna, 1909. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, Suffragette Madonna, 1909. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Many anti-suffrage images centered male anxieties over the gendered division of household labor and the proper role of women. In 1909’s “Suffragette Madonna,” the artist used a tongue-in-cheek inversion of the Virgin Mary to bemoan the martyrdom of a father forced to take care of his child.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, When Women Vote, 1906. Courtesy of Woman and Her Sphere and the Elizabeth Crawford Collection.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, When Women Vote, 1906. Courtesy of Woman and Her Sphere and the Elizabeth Crawford Collection.

Another example of the numerous anti-suffrage postcards in circulation at the turn of the century showed what would happen “When Women Vote.” It portrays a nightmare of outraged masculinity: A harried father is relegated to laundry and childcare while his wife smokes, plays cards, munches chocolate, and complains about what a “lazy old wretch” he is to her friends.

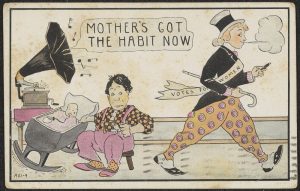

In “Mother’s Got the Habit Now,’ a confident woman strides out to vote, leaving her husband at home with the baby. From her daring trousers to her cigar-puffing smirk, she exemplifies male fears about how women’s suffrage would undoubtedly destroy the traditional family.[58]

Photo credit: Artist unknown, Mother’s Got the Habit Now, March 2, 1913, postcard. Courtesy of the Johns Hopkins University Library.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, Mother’s Got the Habit Now, March 2, 1913, postcard. Courtesy of the Johns Hopkins University Library.

Perhaps ironically for those patriarchy-defenders, the love that queer women had for each other – and their determination to live their lives on their own terms – did indeed help sustain the suffrage movement.[59] Alice Dunbar-Nelson, a Black suffrage organizer and writer, described a thriving lesbian and bisexual subculture among Black activists and wrote candidly about her own romantic and sexual experiences with other women.[60] And in her landmark study To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America, historian Lillian Faderman persuasively argues that it was precisely these supportive partnerships between women that made many social reforms – including the fight for suffrage – a reality.[61]

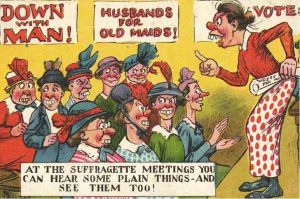

Women’s value as objects of sexual attraction for men was often invoked as anti-suffrage artists depicted the presumed hideousness of the suffragists. “At the suffragette meetings you can hear some plain things – and see them too!” brayed one anti-suffrage postcard.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, At the Suffragette Meetings You Can Hear Some Plain Things, 1910. Courtesy of BBC History Magazine.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, At the Suffragette Meetings You Can Hear Some Plain Things, 1910. Courtesy of BBC History Magazine.

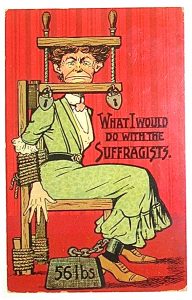

Violence against suffragists was also frequently stoked in the popular postcards and cartoons of the day.[62] One postcard from the early 1900s, titled “What I Would Do with the Suffragists,” caricatures the suffragist as unattractive and shows her bound to a chair and chained to a “56-lbs” weight, her face locked into a vise to prevent her from speaking. The casual cruelty and violence in these images exemplify the rampant misogyny pervading women’s lives at the turn of the 20th century.[63]

Photo credit: Artist unknown, What I Would Do With the Suffragettes. Courtesy of Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia.

Photo credit: Artist unknown, What I Would Do With the Suffragettes. Courtesy of Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia.

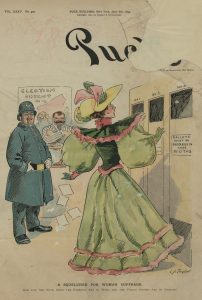

Despite the supposed ugliness of the suffragette, conventionally beautiful or fashionable women were hardly free from jokes at their expense. Women’s clothes changed rapidly in the decades before and after the start of the 20th century as feminists fought for “dress reform” and the height of fashion often remained impractical.[64] Naturally, fashion was a frequent angle of attack for the anti-suffrage camp as well as a signifier for the confident, liberated, and pro-suffrage “New Woman.”[65] An 1894 cover of Puck, titled “A Squelcher for Woman Suffrage,” posited that the latest puffed-sleeve dresses would physically prevent women from entering the voting booth!

Photo credit: Charles Jay Taylor, “A squelcher for woman suffrage“, Puck Magazine 35, no. 900 (June 6, 1894), Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo credit: Charles Jay Taylor, “A squelcher for woman suffrage“, Puck Magazine 35, no. 900 (June 6, 1894), Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Fulfilling Victory’s Promise

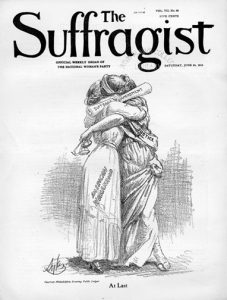

When the Nineteenth Amendment was finally ratified by the requisite number of states, the June 1919 cover of The Suffragist showed “Justice” tightly embracing “American Womanhood” in an image that throbs with the desperate relief that many activists felt in that moment. In 1920, suffrage leader Anna Shaw wrote to her longtime partner Lucy Anthony that they had earned “freedom from worry” and could finally “enjoy the glory” of the rest of their lives.[66]

Photo credit: Unknown, “At Last,” The Suffragist, June 21, 1919. Courtesy of Bryn Mawr College Library.

Photo credit: Unknown, “At Last,” The Suffragist, June 21, 1919. Courtesy of Bryn Mawr College Library.

“At Last,” indeed – though only for some. Women of color are not represented in either character, and today the fight for Americans of color to freely access the ballot is still very much underway.[67]

Despite those impediments, the historic election of Kamala Harris as Vice President is a mark of how far the nation has come. Just 100 years after some women, most of whom were white, gained the right to vote, the United States has elected the first Black person, the first South Asian person, and the first woman ever to occupy its second-highest office.[68] Two contemporary artists have responded by placing Ms. Harris along a continuum of history, as both culmination and continuation of a struggle that began long before she was born.

Photo Credit: Good Trubble and Bria Goeller. That Little Girl Was Me. Courtesy of Good Trubble and the Los Angeles Times.

Photo Credit: Good Trubble and Bria Goeller. That Little Girl Was Me. Courtesy of Good Trubble and the Los Angeles Times.

In this viral illustration by the company Good Trubble and artist Bria Goeller, Harris casts the shadow of Ruby Bridges, the young Black girl who integrated the New Orleans school system. Ruby’s silhouette appears to be based on her depiction in Norman Rockwell’s 1964 painting “The Problem We All Live With.”[69] By invoking Rockwell’s famous image of young Ruby’s bravery in the face of systemic racism and segregation, Goeller places Harris in context with the many women and girls who fought for civil rights before her. Even more specifically, the title of the image,“That Little Girl Was Me” – was intended to refer to Harris’ own comments about her childhood experience with busing as schools in her native Oakland worked to integrate.[70]

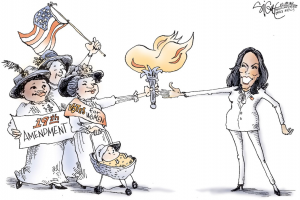

Photo credit: Signe Wilkinson, “Kamala wins the vote,” Cartoon, The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 2020.

Photo credit: Signe Wilkinson, “Kamala wins the vote,” Cartoon, The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 2020.

In “Kamala wins the vote,” published just after it became clear that Biden and Harris would win in Pennsylvania, Pulitzer-prize winning Philadelphia Inquirer editorial cartoonist Signe Wilkinson used a playful double meaning to celebrate Harris’ historic victory. The suffragists who are literally passing the torch to Harris “won the vote” – as in, the right to vote – and now Harris herself has won a national election, apparently largely thanks to a diverse coalition of women voters.[71]

In the cartoon, Harris is depicted in the white pantsuit and silk pussy-bow blouse she donned for her victory speech on November 7. Fashion critic Vanessa Friedman noted that the outfit referenced the history of both women’s suffrage and women in the workplace, a sartorial statement “stretching from the suffragists through Geraldine Ferraro, Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi and the women of Congress.”[72]

Wilkinson herself is a notable “first” in her own right as the first woman ever to win a Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning and one of only three women editorial cartoonists to be nationally syndicated.[73] Her latest book, Herstory, collects 19 cartoons that explore women’s issues in honor of the Nineteenth Amendment’s centennial. In an email exchange, she mentioned her deep interest in suffrage cartoons and showed an astute appreciation of their impact.

“These women didn’t draw for prizes,” she wrote. “They drew to change history – and succeeded!”[74]

As we push to fulfill the Nineteenth Amendment’s promise, especially for women of color, suffrage’s vivid visual history illuminates the progress we’ve made – and the distance left to go.

-END-

[1] Annette Gordon-Reed, “Thomas Jefferson’s Vision of Equality Was Not All-Inclusive. But It Was Transformative,” TIME, February 20, 2020, https://time.com/5783989/thomas-jefferson-all-men-created-equal/.

[2] Ariela Gross and Alejandro de la Fuente, “Citizenship Once Meant Whiteness. Here’s How That Changed,” The Washington Post, July 18, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/18/citizenship-once-meant-whiteness-heres-how-that-changed/.

[3] Vanessa Taylor, “100 Years After Women’s Suffrage, US Voters Still Face Countless Barriers,” Vice, August 3, 2020, https://www.vice.com/en/article/ep4myz/100-years-after-womens-suffrage-us-voters-still-face-countless-barriers.

[4] Kenneth Florey, Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia: An Illustrated Historical Study (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2013).

[5] Johanna Drucker, “Industrialization of Print,” in History of the Book, (Los Angeles: UCLA Library, n.d.), https://hob.gseis.ucla.edu/HoBCoursebook_Ch_9.html.

[6] David M. Hekin, “Becoming Postal: A Communications Revolution in America,” in The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth-Century America, (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007), https://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/327205.html.

[7] Anna Diamond, “Fighting for the Vote With Cartoons,” The New York Times, August 14, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/14/us/suffrage-cartoons.html.

[8] John M. Coward, “Making Sense of Savagery: Native American Cartoons in The Daily Graphic,”

Visual Communication Quarterly 19, issue 4 (2012): 200-215, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15551393.2012.735572.

[9] Brian Resnick, “Racist Anti-Immigrant Cartoons From the Turn of the 20th Century,” The Atlantic, November 21, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/11/racist-anti-immigrant-cartoons-from-the-turn-of-the-20th-century/383248/.

[10] Clare Corbould, “The Herald Sun’s Serena Williams Cartoon Draws on a Long and Damaging History of Racist Caricature,” The Conversation, November 11, 2020, https://theconversation.com/the-herald-suns-serena-williams-cartoon-draws-on-a-long-and-damaging-history-of-racist-caricature-102982.

[11] David H. Gans, “The 14th Amendment Was Meant to Be a Protection Against State Violence,” The Atlantic, July 19, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/07/14th-amendment-protection-against-state-violence/614317/.

[12] Steve Innskeep and Lori Ginzburg, “For Stanton, All Women Were Not Created Equal,” NPR, July 13, 2011, https://www.npr.org/2011/07/13/137681070/for-stanton-all-women-were-not-created-equal.

[13] History.com Staff, “Chinese Exclusion Act.” History.com, August 24, 2018, last modified September 13, 2019, https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/chinese-exclusion-act-1882.

[14] “Chinese Exclusion Act,” The African American Policy Forum, accessed November 23, 2020, https://aapf.org/chinese-exclusion-act.

[15] Robert Barde, “An Alleged Wife: One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era,” Prologue 36, no. 1 (Spring 2004), https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2004/spring/alleged-wife-1.html.

[16] “Chinese Girl Wants To Vote,” New-York Endowment Tribune, April 13, 1912, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1912-04-13/ed-1/seq-3/.

[17] Yuning Wu, “Chinese Exclusion Act,” In Encyclopædia Britannica, Article published November 22, 2019, accessed November 23, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chinese-Exclusion-Act.

[18] Thomas Nast, “Move on!” Has the Native American no rights that the naturalized American is bound to respect?, April 22, 1871, The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001696066/.

[19] Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393, 407 (1857).

[20] “Getting the Vote: Native Americans.”

[21] “Not All Women Gained the Vote in 1920,” PBS, July 6, 2020, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/vote-not-all-women-gained-right-to-vote-in-1920/.

[22] Diamond, “Fighting for the Vote.”

[23] John Henry Adams, The Crisis 12 no. 1 (May 1916): 43, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435023476583&view=image&seq=49&q1=woman%20to%20the%20rescue.

[24] Martha S. Jones, “Black Women’s 200 Year Fight for the Vote,” PBS, June 3, 2020, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/vote-black-women-200-year-fight-for-vote/.

[25] Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915).

[26] Alan Greenblatt, “The Racial History Of The ‘Grandfather Clause,’” NPR, October 22, 2013, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/10/21/239081586/the-racial-history-of-the-grandfather-clause.

[27] Martha S. Jones, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (New York: Basic Books, 2020), 202.

[28] Cécile Yézou, “Black Women’s Resistance to Sexual Violence,” Black Perspectives, March 22, 2019, https://www.aaihs.org/black-womens-resistance-to-sexual-violence/.

[29] Booker T. Washington, “The Awakening of the Negro,” The Atlantic, September 1896, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1896/09/the-awakening-of-the-negro/305449/.

[30] W.E.B. Dubois, “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others,” in The Souls of Black Folk (Project Gutenberg, 2008), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/408/408-h/408-h.htm#chap03/.

[31] “Woodrow Wilson and Race in America,” PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/wilson-and-race-relations/.

[32] Adrienne LaFrance and Vann R Newkirk II, “The Lost History of an American Coup D’État,” The Atlantic, August 12, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/08/wilmington-massacre/536457/.

[33] “(1866) Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, ‘We Are All Bound Up Together,’” BlackPast, November 7, 2011, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/speeches-african-american-history/1866-frances-ellen-watkins-harper-we-are-all-bound-together/.

[34] “Sojourner Truth: ‘Ain’t I a Woman?’, December 1851,” Internet History Sourcebooks, Fordham University, August 1997, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/sojtruth-woman.asp.

[35] Innskeep and Ginzburg, “For Stanton, All Women Were Not Created Equal.”

[36] “(1866) Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, ‘We Are All Bound Up Together.’”

[37] Allison Lange, “Suffragists Organize: National Woman Suffrage Association,” National Women’s History Museum, Fall 2015, http://www.crusadeforthevote.org/nwsa-organize.

[38] Sojourner Truth, “Ain’t I a Woman?”, December 1851.

[39] Henry S. Allen, letter to the editor, “Justice for Woman,” The New York Times, March 6, 1900, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1900/03/06/101051398.html?pageNumber=8.

[40] “(1866) Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, ‘We Are All Bound Up Together.’”

[41] Ibid.

[42] Diamond, “Fighting for the Vote.”

[43] Stephanie Hall, “Symbolism in the Women’s Suffrage Movement.” Library of Congress, August 24, 2020, https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2020/08/symbolism-in-the-womens-suffrage-movement/.

[44] “Ohio Woman Suffrage Association,” Ohio History Central, accessed October 30, 2020.

[45] Diamond, “Fighting for the Vote with Cartoons.”

[46] “Women’s Suffrage in the Progressive Era,” The Library of Congress, accessed October 11, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/progressive-era-to-new-era-1900-1929/womens-suffrage-in-progressive-era/.

[47] Leila McNeill, “This 19th Century ‘Lady Doctor’ Helped Usher Indian Women Into Medicine,” Smithsonian Magazine, August 24, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/19th-century-lady-doctor-ushered-indian-women-medicine-180964613/.

[48] “University Extension; And the Part That Women Are Taking in the Movement.” The New York Times, December 24, 1893, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1893/12/24/109716192.html?pageNumber=18

[49] Melissa De Witte, “Some Suffragists in the 19th Century Exploited Existing Stereotypes of the Period to Advance Their Cause, Says Stanford Legal Historian,” Stanford News, August 12, 2020, https://news.stanford.edu/2020/08/12/left-out-of-the-vote/.

[50] Steven A. Farber, “U.S. Scientists’ Role in the Eugenics Movement (1907–1939): A Contemporary Biologist’s Perspective,” Zebrafish 5, no. 4 (December 2008), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2757926/.

[51] Chris Uggen, Ryan Larson, Sarah Shannon, and Arleth Pulido-Nava, “Locked Out 2020: Estimates of People Denied Voting Rights Due to a Felony Conviction,” The Sentencing Project, October 30, 2020, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/locked-out-2020-estimates-of-people-denied-voting-rights-due-to-a-felony-conviction/.

[52] James Baldwin, “Cornelia’s Jewels,” American Literature, https://americanliterature.com/author/james-baldwin/short-story/cornelias-jewels.

[53] Elaine Weiss, “Women Would Abolish Child Labor (and Other Anti-Suffrage Excuses),” The New York Times, August 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/26/opinion/sunday/suffrage-19th-amendment.html.

[54] Meagan Day, “How Class-Conscious Women Garment Workers Shaped the Movement for Women’s Suffrage,” Jacobin, August 26, 2020, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/08/women-suffrage-vote-19th-amendment-suffragists.

[55] Mark Twain, “Female Suffrage – Views of Mark Twain,” The Weekly News-Democrat, March 22, 1867, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/2823742/mark-twain-satire-against-womans.

[56] “Sex and Suffrage,” editorial, The New York Times, July 23, 1867, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1867/07/23/80244198.html?pageNumber=4.

[57] Dr. Roann Barris, “Art Responds to Women’s Suffrage: Pro and Con,” Radford University, accessed October 30, 2020, https://www.radford.edu/rbarris/Women%20and%20art/amerwom05/suffrageart.html.

[58] Susan B. Anthony, “Children of Women Suffragists,” The New York Times, January 1, 1883, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1883/01/01/103432907.html?pageNumber=3.

[59] Maya Salam, “How Queer Women Powered the Suffrage Movement,” The New York Times, August 14, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/14/us/queer-lesbian-women-suffrage.html?searchResultPosition=4.

[60] Wendy Rouse, “The Very Queer History of the Suffrage Movement,” Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission, June 9, 2020, https://www.womensvote100.org/the-suff-buffs-blog/2020/6/9/the-very-queer-history-of-the-suffrage-movement?fbclid=IwAR2uFzei307YAkprNa7V-35ztQQMAhxJtWOqoshLxHimtOG0Y-BKl73Ha54.

[61] Lillian Faderman, To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America – A History (Mariner Books, 2000), 6.

[62] Therese O’Neill, “12 Cruel Anti-Suffragette Cartoons,” Mental Floss, June 21, 2015, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/52207/12-cruel-anti-suffragette-cartoons.

[63] Marina Koren, “Why Men Thought Women Weren’t Made to Vote,” The Atlantic, July 11, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/07/womens-suffrage-nineteenth-amendment-pseudoscience/593710/.

[64] “Mrs. Jenness-Miller is Dead at Age of 78,” The New York Times, August 10, 1935, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1935/08/10/93693122.html?pageNumber=13.

[65] Durdona Gaibova, “Votes & Petticoats,” The Fashion of Suffrage, Johns Hopkins University, accessed November 2, 2020, https://exhibits.library.jhu.edu/omeka-s/s/VotesAndPetticoats/page/the-fashion-of-suffrage.

[66] Faderman, 59.

[67] Vann R. Newkirk II, “Voter Suppression Is Warping Democracy,” The Atlantic, July 17, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/07/poll-prri-voter-suppression/565355/.

[68] Chelsea Janes, “Americans React to Kamala Harris’s Historic Victory: ‘Look Baby, She Looks like Us.’” The Washington Post, November 7, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/reactions-kamala-harris-vice-president/2020/11/07/8eaad904-213a-11eb-90dd-abd0f7086a91_story.html.

[69] Norman Rockwell, The Problem We All Live With, 1964, oil on canvas, 36” x 58,” Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, http://www.nrm.org/thinglink/text/ProblemLiveWith.html.

[70] Erika D. Smith, “The Story You Haven’t Heard about That Viral Image of Kamala Harris and Ruby Bridges,” Los Angeles Times, November 13, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-11-13/election-2020-kamala-harris-ruby-bridges-illustration-sacramento.

[71] Erin Delmore, “This Is How Women Voters Decided the 2020 Election,” NBC News, November 13, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/know-your-value/feature/how-women-voters-decided-2020-election-ncna1247746.

[72] Vanessa Friedman, “Kamala Harris in a White Suit, Dressing for History,” The New York Times, November 8, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/08/fashion/kamala-harris-speech-suffrage.html.

[73] Brigid C. Harrison, and Ann Telnaes, “Interview with Ann Telnaes,” PS: Political Science and Politics 40, no. 2 (April 2007): 234.

[74] Signe Wilkinson, email message to author, November 17, 2020.