Historical Practice and Case Law Support Broad Congressional Oversight Powers

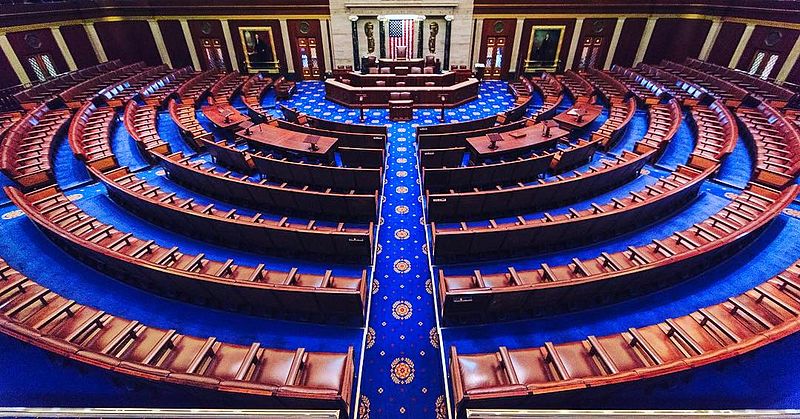

Earlier this month, there was a leadership change in the House of Representatives, and this change has led to considerable discussion about what role the 116th Congress will play in investigating and holding accountable the Trump Administration. The simple answer is that the House could, if it chooses, play a significant role, investigating everything from misuse of funds by cabinet officials, to connections between President Trump’s campaign and Russia, to whether the President or other high-ranking officials are improperly benefitting financially from their offices, to whether the Executive Branch is appropriately enforcing environmental and other public health and safety laws.

In a new Issue Brief, my colleagues at the Constitutional Accountability Center and I detail the history of legislative investigations, case law approving Congress’s vast power to investigate, and the ways in which Congress can enforce subpoenas to make its investigations effective and to hold the Executive Branch accountable. At every turn, it is clear that Congress’s power to investigate is broad, and that this power to investigate includes numerous tools to hold this Administration to account.

Our Issue Brief makes three principal points. First, there is a lengthy history of legislatures engaging in robust investigations. As early as the Seventeenth Century, British Parliament investigated issues as diverse as the conduct of the army in “sending Relief” into Ireland during war, “Miscarriage in the Victualing of the Navy,” and the imposition of martial law by the commissioner of the East India Company. Similarly, colonial legislatures exercised broad investigatory powers. For example, the Pennsylvania assembly had “a standing committee to audit and settle the accounts of the treasurer and of the collectors of public revenues,” which had the “full Power and Authority to send for Persons, Papers and Records by the Sergeant at Arms of this House.”

Following in this tradition, the United States Congress exercised robust investigatory powers early in the Republic’s history. In March 1792, the House created a special committee to inquire into the defeat of the army under Major General St. Clair, and the debate of that measure reflects that Congress believed it should investigate the matter itself, rather than directing the President to do so. It is noteworthy that James Madison and four other members of the Constitutional Convention all voted in favor of a Congressional committee to investigate.

Moreover, some early Congressional investigations focused specifically on the President and his Cabinet. For example, in 1832, the House created a committee to discover “whether an attempt was made by the late Secretary of War, John H. Eaton, fraudulently to give to Samuel Houston — a contract — and that the said committee be further instructed to inquire whether the President of the United States had any knowledge of such attempted fraud, and whether he disapproved of the same; and that the committee have power to send for persons and papers.”

Second, in addition to long-standing historical practice, the Supreme Court has recognized that Congress has robust authority to investigate as part of its extensive Article I power to legislate. In 1927, in McGrain v. Daugherty, the Court considered whether the Senate could, in the course of an investigation regarding the Department of Justice, compel a witness—in that case, the brother of the Attorney General—to appear before a Senate committee to give testimony. The Court said yes, reasoning that “[a] legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change; and where the legislative body does not itself possess the requisite information—which not infrequently is true—recourse must be had to others who do possess it.” Further, the Court noted that “some means of compulsion are essential to obtain what is needed.”

The Court has reiterated that holding since. In its 1955 decision in Quinn v. United States, it noted that there can be “no doubt as to the power of Congress, by itself or through its committees, to investigate matters and conditions relating to contemplated legislation.” And in Watkins v. United States in 1957, the Court reiterated that “the power of the Congress to conduct investigations is inherent in the legislative process,” that it “includes surveys of defects in our social, economic or political system for the purpose of enabling the Congress to remedy them,” and that “[i]t comprehends probes into departments of the Federal Government to expose corruption, inefficiency or waste.”

Third and finally, as our Issue Brief details, Congress has a variety of tools it can use to enforce subpoenas for documents and testimony where it needs those materials to effectively investigate, and we focus particular attention on one of those: Congress’s ability to file a civil action in federal court demanding that a witness comply with a subpoena. Two recent cases—one that arose during the George W. Bush Administration and one during the Obama Administration—both approved of this method of enforcement.

During the Bush Administration, the House of Representatives filed a civil suit seeking to enforce a subpoena of two White House officials, Josh Bolten and Harriet Miers, as part of the House’s investigation into the resignation of nine United States Attorneys. The Executive Branch had asserted executive privilege over certain documents and testimony by these individuals. A district court in Washington, DC held that the House had standing to sue to enforce the subpoena because it was conducting a “broader inquiry into whether improper partisan considerations have influenced prosecutorial discretion,” and it “defies both reason and precedent to say that the Committee, which is charged with oversight of DOJ generally, cannot permissibly employ its investigative resources on this subject.” Moreover, the court noted that enforcing a subpoena is a routine judicial task, and that courts are the final arbiters on assertions of privilege.

A second case raising the same issues came before the D.C. district court during the Obama Administration, and a second Judge permitted a case brought by the House of Representatives to enforce a subpoena to move forward. That case arose out of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform’s investigation of the so-called Fast and Furious operation, and the Justice Department’s refusal to turn over certain documents regarding the operation. Like the prior district court, this court held that the House had standing and that the political question doctrine did not bar the suit because the case “involv[ed] the application of a specific privilege to a specific set of records responsive to a specific request, and the lawsuit d[id] not invite the court to engage in the broad oversight of either of the other two branches.”

In sum, it is long-settled—both in practice and in the Supreme Court’s case law—that Congress’s power to investigate is co-extensive with its power to legislate, including investigations of the Executive Branch and Executive Branch officials. Moreover, Congress has a variety of tools it can use to enforce subpoenas for documents and testimony by Executive Branch officials where it needs those materials to effectively investigate and legislate. These tools include bringing a civil suit in district court, something that the House successfully did during both the Bush and Obama Administrations. All these investigatory powers are sure to be important as the new Congress begins to exercise the oversight authority that is both its right and its responsibility.