Originalism, Fauxriginalism, and Embracing the Constitution

Conservatives have long maintained that originalism, their preferred method of constitutional interpretation, is the only true way of honoring the Constitution. There are a lot of different permutations of originalism, but most share a belief that the Constitution must be interpreted based on the original public meaning of its text at the time of the document’s ratification. Conservatives argue that this interpretive method is rooted in fidelity to our nation’s founding charter, and they tell us that they employ this method to land wherever the text leads them. Of course, conveniently for conservatives, where it has purportedly most often led them is to conservative outcomes.

If it were true that originalism most often led to conservative results, progressives would have ample reason to feel conflicted about their relationship to the Constitution’s text. However, it’s not true. We need not choose between progressive values (like true equality, meaningful due process, and a fully participatory Democracy) and fidelity to the Constitution’s text. It’s a forced and false choice. That’s because the words of the Constitution—along with the history and values that shed light upon the meaning of ambiguous parts of the text—are progressive at their core.

At a time when monarchies were the norm in much of the world, our Constitution’s Framers created a democratic system based on the sovereignty of “We the People,” and a system of checks and balances to better secure liberty and prevent any one branch from seizing too much power. Our Constitution’s Framers devised a federal government with broad powers to solve national problems, created an independent judiciary to enforce the Constitution and maintain the rule of law, and wrote the Bill of Rights to ensure respect for liberty.

Of course, for important reasons, our founding charter is, and always has been, a work in progress. Our original Constitution was far from perfect, as it sanctioned slavery and permitted massive violations of fundamental rights by state governments. The text has been amended numerous times in order to realize more fully the promise of our great nation. Perhaps the clearest example of this is provided by the Reconstruction Amendments (the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments), which are so foundational that they are often considered our “second founding.” These amendments served as an acknowledgment that the Declaration of Independence’s promises had not been kept when it came to our African American brothers and sisters, and that the original Constitution’s promise of liberty had been betrayed by its acceptance of slavery. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery; the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed birthright citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States and wrote into the Constitution sweeping new guarantees that required state and local governments to respect the liberty, dignity, and equality of all persons; and the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed the right to vote free from racial discrimination. Considered together, the Reconstruction Amendments represent an attempt to move our Constitution one step closer to the Declaration of Independence’s ideals of inalienable rights and equality.

Our founding document’s step-wise progression traces an arc of constitutional progress, bringing us, amendment by amendment, closer to true equality and meaningful inclusion. There are other steps along that arc—such as the Nineteenth Amendment (prohibiting gender discrimination in voting) and the Twenty-Sixth Amendment (lowering the voting eligibility age from 21 to 18 years of age and prohibiting voting discrimination on the basis of age)—and there may be more steps ahead of us. Because it was a document that was not designed to be altered lightly, when it might next be amended and what topic rises to such importance remains unclear. What is clear is that each new amendment’s ratification provides a new moment to gauge meaning. Amendments don’t stand alone, but rather function as a critical part of the text they amend, forcing us to read not only the new words, but to understand their interaction with the words that came before them. True fidelity to the Constitution requires fidelity to the whole text, its history, and its values.

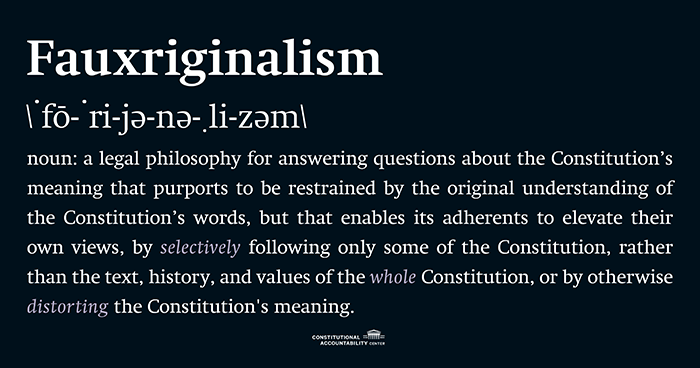

And that’s why progressives have not been fighting originalism; we have been fighting fauxriginalism. Fauxriginalism distorts the meaning of the Constitution, often by focusing selectively on some parts of the document, rather than by looking at the text, history, and values of the whole Constitution. Conservatives like to claim that originalism leads them to conservative results, but that’s because they too often give a cramped meaning to the Constitution’s text and ignore the constitutional history and values that help elucidate what that text means. In truth, conservatives have been a bit like the kid in our grade school class who delivered a book report, but who had only read the first chapters of the book—and didn’t even read them that carefully. Just as we were skeptical then, we should be skeptical now. What we are reacting to is not the text, but what we’ve been told about the text by an unreliable narrator who isn’t telling us the complete story. It’s time for progressives to call out fauxriginalism for what it is—and embrace the originalism that looks to the text, history, and values of the whole Constitution. Our country depends on it.